by Sean O’Toole

Presented by Afterimage at The Labia Theatre, Cape Town, 19 February 2025

It is nearly two years since artist Dale Lawrence presented his short film Between Lives (2023) in his solo exhibition Midden at Whatiftheworld Gallery. An episodic and oftentimes resistant film about grief, mourning and disconnection in this age of digital distraction, Between Lives features a half-dozen or so video clips, mostly unedited takes filmed on a smartphone in South Africa and the United States, that Lawrence has paired with voiceovers generated by text-to-speech bots fed with an irregular diet of online content (news articles, an advert for a Zombie game encountered on Instagram, personal correspondence).

The voiceover for the first sequence, a mesmerised top-down view of accumulated sea foam, includes a terse list of statements in the negative. Culled from News 24 articles, they include the phrases “no accountability”, “no structure”, “no responses”, “no money”. This succinct voiceover operates somewhat like a manifesto of means and intentions. When I say manifesto, I think particularly of dancer and experimental filmmaker Yvonne Rainer’s No Manifesto (1965). “No to virtuosity,” stipulated Rainer. Check IRO Lawrence’s film. “No to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer.” Check again.

The adjective “experimental” is a wildly overused qualifier in the art world, but it hints at a truth about Lawrence’s elliptical and challenging film. It is a product of experiment. “I started filming bits and pieces with no real intention of where it was going,” Lawrence explained before the film’s recent screening at the Labia Theatre, the sixth in a series of viewings curated by Ben Albertyn and Mitchell Gilbert Messina for their biweekly Afterimage programme. “It all came together quite organically.” At some point, however, artistic intention took over.

In its original screening context – in the Buiten Street premises of Whatiftheworld Gallery – Between Lives operated as visual argument motivated by a recurring idea. Lawrence’s exhibition Midden variously explored the role of leftovers and studio debris, be it physical or virtual. The film was shown in a loop alongside haptic things like typed-out copy from a Tesla advert encased in clear packaging tape, a stack of destroyed linocuts made by the artist between 2013 and 2023, as well as a rectangular white column made from cow fat obtained from a butchery in Brooklyn that Lawrence mixed ash from a veld fire near Somerset West into.

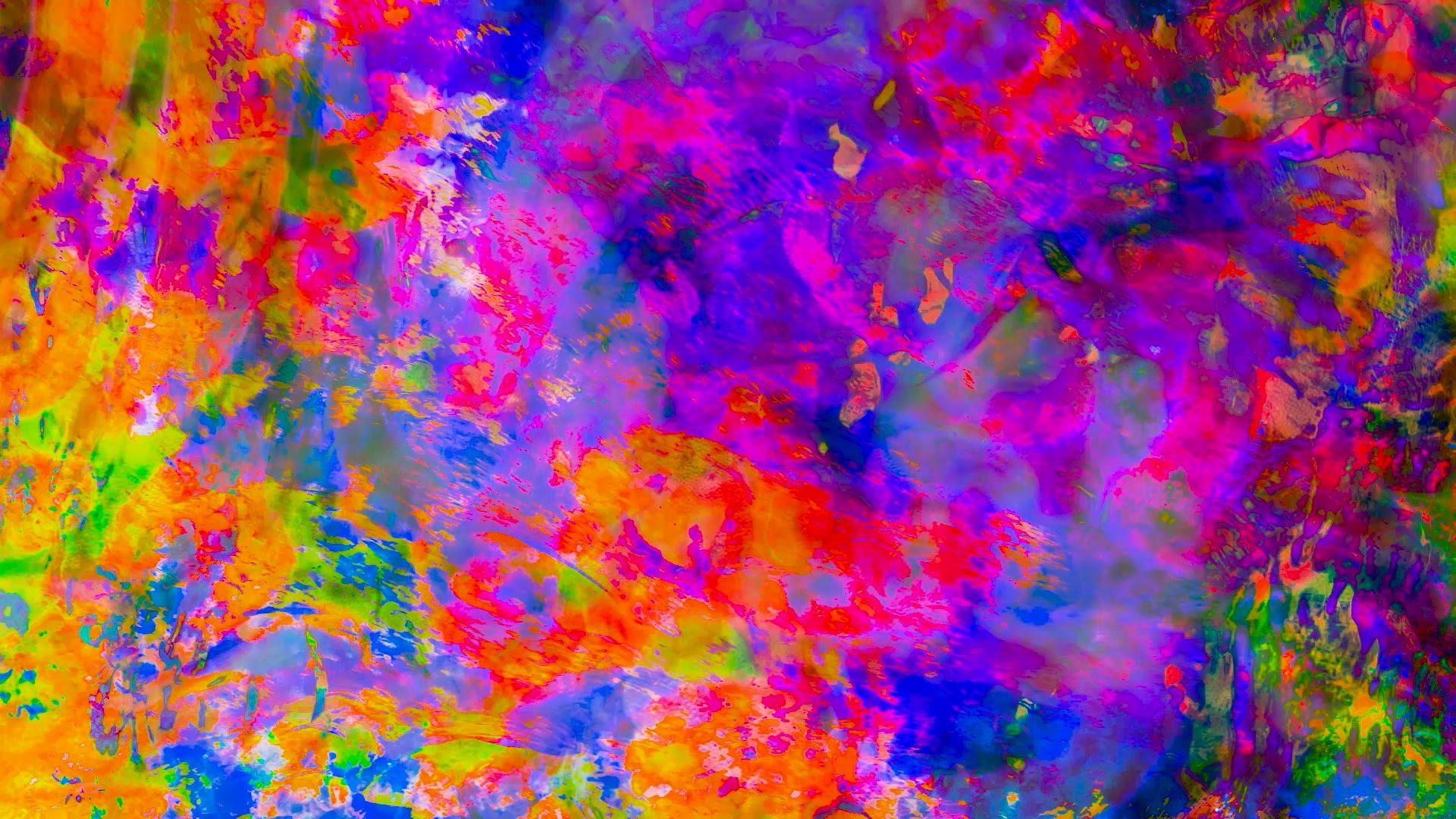

Repetition, the endless loop, is a defining hallmark of how artists’ films are experienced in galleries. By this logic – and it is a logic rather than happenstance – one could, in 2023, have encountered Lawrence’s film at its foamy beginnings, or possibly nearer its Stan Brakhage-like end, where the from-life smartphone realism dissolves into trippy, liquid colour. It really doesn’t matter where one begins when viewing artists’ films in a gallery, because the film will always loop back, clarify itself – that is if the viewer has the fortitude and stamina to stand and wait.

In 2003, the English writer and filmmaker Iain Sinclair, reviewing a curated screening of artists’ films at Tate Britain, mourned the paralysis occasioned by experiencing them in the “clean white rooms” of galleries. “We don’t know how to behave: churchy or cool, sit or stand,” wrote Sinclair. “Art and explanation are divorced.” The workings of this still-prevalent mode of display ensure that thought and dialogue are ceded to the leaflet at the gallery desk. To which Afterimage politely says no: let’s sit, watch and talk – maybe with popcorn and beer in hand.

It is not just the seating, snacks and interested dialogue that distinguished how Lawrence’s film landed in the context of Afterimage. As is protocol, every screening includes additional films selected by the artist. Lawrence chose works by the artists Catching on Thieves and Charlie Prodger. “These two artists resonate with me for their rawness, intimacy and universality of their storytelling,” Lawrence offered at the start. Removed from the original context of the junk pile or midden that framed the original reception of Between Lives, Lawrence’s film was allowed to acquire new resonances and affinities. For me they involved his film’s web 2.0 mechanics.

Catching on Thieves is the pseudonym for an American artist who Lawrence met in 2022 while participating in a residency in Philadelphia facilitated by RAW Académie, the Dakar-based artist organisation founded by Koyo Kouoh. …this stuff… (2024) is a first-person account of survival in gun-crazed America, a blues threnody told mostly in words, not images. The short film presents in a dominant chromatic hue of blue, a la Derek Jarman’s late film Blue (1993).

“I have been shot at too many times,” the voiceover tells in …this stuff…. It takes a while to reach this point. As in Lawrence’s film, made while distractedly doomscrolling while his grandfather was dying, the undergirding trauma that is the subject of …this stuff… is held at a distance, delayed. Deferment and obliquity, successfully treated, can be powerful narrative devices in film. A voice is sufficient to hold attention.

Scottish artist Charlie Prodger’s ambitious film SaF05 (2019) derives its name from a maned lioness documented in the Okavango Delta. The film deploys multiple filmic tools, ranging from film industry cameras to smartphones, webcams and drones. This lends the film a rhetorical quality. The high-def vertical shots of a termite mound, complimented by the technical narration of the site, have an alienating mechanical quality. It is a way to hold and defer the possibly traumatic autobiographical circumstances of the film: the artist’s coming out.

“I’m praying to wake up as a boy,” states the voiceover early into the film. “The Calvinist church is across the road. Stripped back, emotionally withholding. No ornamentation, no fuss. It’s 1984.” Only in the flashback voiceover that is; the cinematic language is very much from now. Old cinema was terrestrial and horizontal; new film is, and has been for a while, airborne and vertical. This verticality has a politics as much as a technical history. “The view from above is a perfect metonymy for a more general verticalization of class relations,” writes Hito Steyerl in her essay In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective (2011). “It is a proxy perspective that projects delusions of stability, safety and extreme mastery onto a backdrop of expanded 3-D sovereignty.”

Other than in the opening chapter of Between Lives, Lawrence does not use vertical perspectives in his film – but its idiosyncratic expression stems from his creative dabbling with, and interest in, surveillance footage. Responding to a question about the elliptical pacing of all three films, Lawrence explained how Between Lives is linked to his earlier habit of habitually filming himself. “It was part of a process of collecting. It started out with filming myself working. I was interested in surveillance, webcams and those kinds of things, public and private weirdness.” In 2020, during the height of the stay-at-home Covid pandemic, he curated the online exhibition Peep Show. Leaning into the big digital pivot, which transformed kitchens and bedrooms into ersatz studios, the exhibition launched with simultaneous live-streamed presentations by the multiple participants.

This interest in the protocols and manners of surveillance coincided with Lawrence’s artistic interest in found things, be it text or ash, haptic junk or “data trash”. In 1994, when Lawrence was six and grunge had just peaked, political scientists Arthur Kroker and Michael A Weinstein coined this phrase, data trash, to account for the immaterial stuff that “crawls out of the burned-out wreckage of the body splattered on the information superhighway.”

Standing in front of his seated audience, Lawrence expanded on how his film was informed by the “weird cacophony of things” that characterises our IRL/URL experiences. While confronting grief and the raw intensity of loss, Lawrence explained, he allowed his thoughts and emotions to be interrupted by “unmediated things flying from all angles,” which is a far nicer phrasing for the digital flotsam that washes up on our virtual beaches daily. Between Lives is his attempt to visualise this experience of being somewhere and nowhere, speaking in a voice that is not his own, using words that are found, feeling grief that is real.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Catching On Thieves, …this stuff…, 2024, film stills.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Charlie Prodger, SaF05, 2019, film stills.

It is nearly two years since artist Dale Lawrence presented his short film Between Lives (2023) in his solo exhibition Midden at Whatiftheworld Gallery. An episodic and oftentimes resistant film about grief, mourning and disconnection in this age of digital distraction, Between Lives features a half-dozen or so video clips, mostly unedited takes filmed on a smartphone in South Africa and the United States, that Lawrence has paired with voiceovers generated by text-to-speech bots fed with an irregular diet of online content (news articles, an advert for a Zombie game encountered on Instagram, personal correspondence).

The voiceover for the first sequence, a mesmerised top-down view of accumulated sea foam, includes a terse list of statements in the negative. Culled from News 24 articles, they include the phrases “no accountability”, “no structure”, “no responses”, “no money”. This succinct voiceover operates somewhat like a manifesto of means and intentions. When I say manifesto, I think particularly of dancer and experimental filmmaker Yvonne Rainer’s No Manifesto (1965). “No to virtuosity,” stipulated Rainer. Check IRO Lawrence’s film. “No to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer.” Check again.

The adjective “experimental” is a wildly overused qualifier in the art world, but it hints at a truth about Lawrence’s elliptical and challenging film. It is a product of experiment. “I started filming bits and pieces with no real intention of where it was going,” Lawrence explained before the film’s recent screening at the Labia Theatre, the sixth in a series of viewings curated by Ben Albertyn and Mitchell Gilbert Messina for their biweekly Afterimage programme. “It all came together quite organically.” At some point, however, artistic intention took over.

In its original screening context – in the Buiten Street premises of Whatiftheworld Gallery – Between Lives operated as visual argument motivated by a recurring idea. Lawrence’s exhibition Midden variously explored the role of leftovers and studio debris, be it physical or virtual. The film was shown in a loop alongside haptic things like typed-out copy from a Tesla advert encased in clear packaging tape, a stack of destroyed linocuts made by the artist between 2013 and 2023, as well as a rectangular white column made from cow fat obtained from a butchery in Brooklyn that Lawrence mixed ash from a veld fire near Somerset West into.

Repetition, the endless loop, is a defining hallmark of how artists’ films are experienced in galleries. By this logic – and it is a logic rather than happenstance – one could, in 2023, have encountered Lawrence’s film at its foamy beginnings, or possibly nearer its Stan Brakhage-like end, where the from-life smartphone realism dissolves into trippy, liquid colour. It really doesn’t matter where one begins when viewing artists’ films in a gallery, because the film will always loop back, clarify itself – that is if the viewer has the fortitude and stamina to stand and wait.

In 2003, the English writer and filmmaker Iain Sinclair, reviewing a curated screening of artists’ films at Tate Britain, mourned the paralysis occasioned by experiencing them in the “clean white rooms” of galleries. “We don’t know how to behave: churchy or cool, sit or stand,” wrote Sinclair. “Art and explanation are divorced.” The workings of this still-prevalent mode of display ensure that thought and dialogue are ceded to the leaflet at the gallery desk. To which Afterimage politely says no: let’s sit, watch and talk – maybe with popcorn and beer in hand.

It is not just the seating, snacks and interested dialogue that distinguished how Lawrence’s film landed in the context of Afterimage. As is protocol, every screening includes additional films selected by the artist. Lawrence chose works by the artists Catching on Thieves and Charlie Prodger. “These two artists resonate with me for their rawness, intimacy and universality of their storytelling,” Lawrence offered at the start. Removed from the original context of the junk pile or midden that framed the original reception of Between Lives, Lawrence’s film was allowed to acquire new resonances and affinities. For me they involved his film’s web 2.0 mechanics.

Catching on Thieves is the pseudonym for an American artist who Lawrence met in 2022 while participating in a residency in Philadelphia facilitated by RAW Académie, the Dakar-based artist organisation founded by Koyo Kouoh. …this stuff… (2024) is a first-person account of survival in gun-crazed America, a blues threnody told mostly in words, not images. The short film presents in a dominant chromatic hue of blue, a la Derek Jarman’s late film Blue (1993).

“I have been shot at too many times,” the voiceover tells in …this stuff…. It takes a while to reach this point. As in Lawrence’s film, made while distractedly doomscrolling while his grandfather was dying, the undergirding trauma that is the subject of …this stuff… is held at a distance, delayed. Deferment and obliquity, successfully treated, can be powerful narrative devices in film. A voice is sufficient to hold attention.

Scottish artist Charlie Prodger’s ambitious film SaF05 (2019) derives its name from a maned lioness documented in the Okavango Delta. The film deploys multiple filmic tools, ranging from film industry cameras to smartphones, webcams and drones. This lends the film a rhetorical quality. The high-def vertical shots of a termite mound, complimented by the technical narration of the site, have an alienating mechanical quality. It is a way to hold and defer the possibly traumatic autobiographical circumstances of the film: the artist’s coming out.

“I’m praying to wake up as a boy,” states the voiceover early into the film. “The Calvinist church is across the road. Stripped back, emotionally withholding. No ornamentation, no fuss. It’s 1984.” Only in the flashback voiceover that is; the cinematic language is very much from now. Old cinema was terrestrial and horizontal; new film is, and has been for a while, airborne and vertical. This verticality has a politics as much as a technical history. “The view from above is a perfect metonymy for a more general verticalization of class relations,” writes Hito Steyerl in her essay In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective (2011). “It is a proxy perspective that projects delusions of stability, safety and extreme mastery onto a backdrop of expanded 3-D sovereignty.”

Other than in the opening chapter of Between Lives, Lawrence does not use vertical perspectives in his film – but its idiosyncratic expression stems from his creative dabbling with, and interest in, surveillance footage. Responding to a question about the elliptical pacing of all three films, Lawrence explained how Between Lives is linked to his earlier habit of habitually filming himself. “It was part of a process of collecting. It started out with filming myself working. I was interested in surveillance, webcams and those kinds of things, public and private weirdness.” In 2020, during the height of the stay-at-home Covid pandemic, he curated the online exhibition Peep Show. Leaning into the big digital pivot, which transformed kitchens and bedrooms into ersatz studios, the exhibition launched with simultaneous live-streamed presentations by the multiple participants.

This interest in the protocols and manners of surveillance coincided with Lawrence’s artistic interest in found things, be it text or ash, haptic junk or “data trash”. In 1994, when Lawrence was six and grunge had just peaked, political scientists Arthur Kroker and Michael A Weinstein coined this phrase, data trash, to account for the immaterial stuff that “crawls out of the burned-out wreckage of the body splattered on the information superhighway.”

Standing in front of his seated audience, Lawrence expanded on how his film was informed by the “weird cacophony of things” that characterises our IRL/URL experiences. While confronting grief and the raw intensity of loss, Lawrence explained, he allowed his thoughts and emotions to be interrupted by “unmediated things flying from all angles,” which is a far nicer phrasing for the digital flotsam that washes up on our virtual beaches daily. Between Lives is his attempt to visualise this experience of being somewhere and nowhere, speaking in a voice that is not his own, using words that are found, feeling grief that is real.

Dale Lawrence, Between Lives, 2023, film stills. |

Catching On Thieves, …this stuff…, 2024, film stills.

Charlie Prodger, SaF05, 2019, film stills.