Further Prototypes

4 Sept.—12 Oct. 19

Solo exhibition at SMITH, Cape Town.

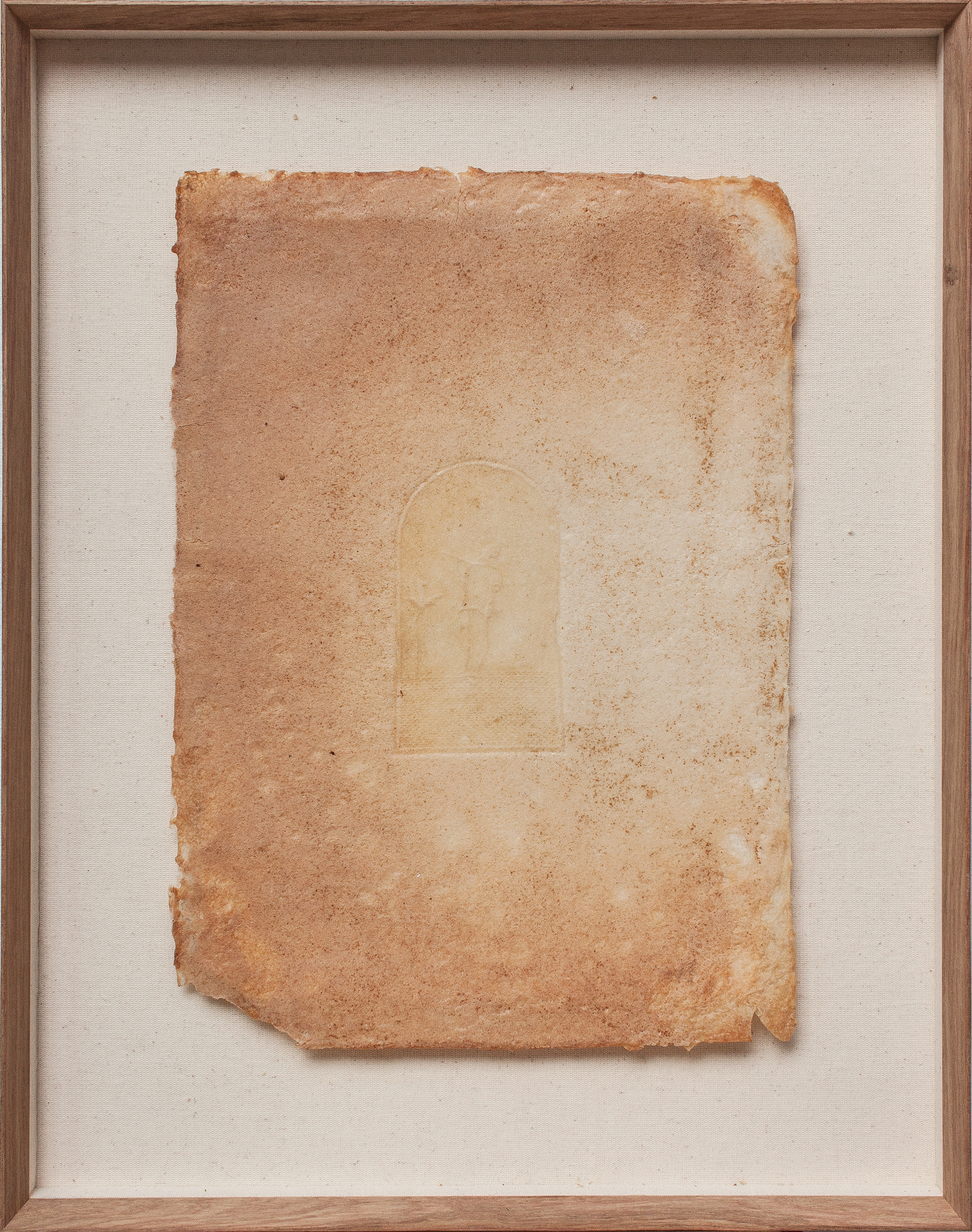

St. Lawrence Handing out the Treasures of the Church (print detail)

Further Prototypes—Dale Lawrence

text by Matthew Freemantle:

When is an artwork finished? At show time? When the artist says so? What if an artist isn’t ‘finishing’ them on purpose, and what if he’s active in the gallery throughout the show? What if he’s asking himself—and us—whether there is such a thing as finished at all?

This is one of many curveballs thrown by Dale Lawrence in Further Prototypes, his third solo show at SMITH, the latest stanza in his wry inquiry into the ambitions of art and its practitioners. With Look Busy (2016) and Another Helping (2017), as with his Art Joburg show Amateur Hour (2018), Lawrence scratched at these ideas, studying the tension between focused intent and wilful abandon. Here, he puts the ideas to theatre.

“Finished is dead,” says Lawrence, who chooses instead to work with the vitality of experimentation. Doing so brings action, change, motion and surprise into another distinctively considered collection of mixed media offerings that this time includes imagery variously scratched into animal fat, drawn onto photocopier glass and printed on bread. There’s also a bath in the gallery and, yes, he will bathe in it. Every day for six weeks.

In Seen and Not Seen, the bathtub work, Lawrence will prove his interactions with it without showing them. We will see solely the evidence of his activity; the memory of it. A wet footprint, perhaps, or a crumpled towel. By repurposing the gallery as a working space, a conduit through which Lawrence passes, he draws attention away from the idea of finished works hanging inert on a wall and towards the lively, uncertain environment from which his works are made.

Throughout the show, Lawrence will be otherwise active in the space, working on his largest canvas to date, the 1.75m x 3.5m Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Large Bathers in situ. These elements of his normal life—the painting, the bathing—help to set the show in a state of flux, placing artmaking as a functional part of the everyday. Here Lawrence draws from German artist Joseph Beuys, who considered art much broader than painting, sculpting and exhibiting. For Beuys, as for Lawrence, the impulse to create is seen as a basic component of human life.

“Completeness and incompleteness coexist. We are never finished. Our routines become rituals and our rituals can degenerate into routines. Art is a form of distilling reality, where grand intentions and everyday mundanities are the subjects—with sometimes overwhelming and sometimes underwhelming results.”

Hercules is Lawrence’s playful tracing of a mashup of two classic scenes with similar compositions by Frederic Lord Leighton and Paul Cézanne. Leighton’s horrified characters, Cezanne’s indifferent bathers and finally Lawrence’s cursory retelling of these stories probes at how the function of art has changed. Art used to need to capture critical and epic moments, later just moments. What do we ask of it now?

That this and other works are in fact or appear ostensibly unfinished stems from a disregard for finality that permeates this collection and can be traced further back. Amateur Hour fleshed out an argument that achievement is subordinate to the act of the pursuit thereto. Then as now, pursuit is Lawrence’s first virtue. To arrive is to abandon pursuit, to be finished. And finished is dead.

Lawrence’s use of masterpieces as source material in the show stems from this notion. His respect for striving over finding sees prototypes as new models of thought. The creative sphere is one for experiment and testing, where new ideas and aesthetics are prototyped and test-driven before being adopted in the real world.

“When a work is considered a masterpiece it implies that an idea has been refined to the point of absolute completion and perhaps exhaustion, leaving it short of much of the vitality of the prototype.”

Lawrence’s most pointed jab at this is the work St. Lawrence Handing out the Treasures of the Church, where he treats a photocopy machine’s glass as a printing plate. Viewers of the work will be able to print out a copy of the famous scene, as artist and device stage a modern parody on the doling out of churchly treasures. The cumbersome photocopier is the artist himself, a dubious intermediary through which an original and pure thought must traverse. Repetitions mean diminishing returns. More is less.

“If art is a means by which to pay homage to inspiration it is also proof of the inability of human beings to accurately express the purity of that inspiration. The observer principle suggests that it is impossible to observe a phenomenon without changing it. Art is an interference.”

Portrait of Ideal Self as St. Paul the Hermit, Except Not so Poor and Hungry and Naked and Lonely and Cold is a relief print on a sheet of bread, akin in both substance and design to the communion offering but depicting a figure engaged in a leisure activity. Bread is a basic unit of substance and signifier of spiritual nourishment, yet only represents meaning. It has none in and of itself.

St. Lawrence? Communion bread? Has Lawrence gone all religious on us? The gallery is, after all, art’s church. This is where a form of aesthetic communion is practiced. This is where we gather to drink wine and hear nominated spokespeople muse on the meaning of it all. The substance of the offering depends in some part to the faith we place in the institution that houses it, and of course the person handing us the sacrament. Communion bread is either metaphysical and full of meaning, or vacuous and in dire need of some Marmite.

Or, as Lawrence suggests, lightly salted like a Lay’s crisp. Perhaps the crowning piece of the show is another remake, this time a riff on the 'Tragedia Civile' by Jannis Kounellis. Lawrence uses Lay’s crisp packets where Kounellis used gold leaf to festoon a wall signifying the accomplishments of the past. Lawrence replaces the original’s hook, hat and overcoat with a bowl of Lay’s lightly salted crisps lying on the table for consumption, while a mobile phone lies charging on the shelf instead of a paraffin lamp. This self-administering of communion, a modern offering of no substance in an age of cheap imitation and distraction, wonders at the depth of our dubious relationship with conveyors of meaning.

But accomplishment implies some measure of success and finality, and we know how Lawrence feels about those things. His title for the installation, Tragedy of the Rainbow Warriors, mashes up the original with a newspaper headline marking a supposedly seminal moment in recent South African history. Nelson Mandela, dressed in a Springbok jersey, hands captain Francois Pienaar the 1995 Rugby World Cup trophy. Here is a moment that aimed to tell us something had ended. But was this the end—or the beginning—of anything?

Clearly, Lawrence detects a kind of idiocy in viewing this or any moment as a conclusion or resolution. “We were supposed to feel like something had been solved. We were offered absolution from our sins, cheap closure in a flash. The truth was something a lot less certain.”

Lawrence doesn’t miss this opportunity for another witticism. Noting that we lay our crisps onto our tongues like communion wafers, he nominates a Western brand as our priest. As Apartheid ended and sanctions were lifted, we South Africans were rewarded with a deluge of attractive but empty gifts from the West. The Gods were good to us.

If Lawrence is playing with his use of the pedestal it is more as jester than preacher. Like a king’s clown he agitates, entertains and excites, making himself vulnerable, present and unguarded. Lawrence’s work can also be downright funny. A found ceramic vase lies shattered on the floor beneath its pedestal, surrounded by a handful of rubber bands, the dull accoutrements it was used to contain. The ornate is reduced to a vessel for cheap, functional detritus. A vessel, grand and full of potential, tragically reduced to its base utility. But is an ornament less impressive when it is being used?

With Nameless and Friendless, Lawrence removes the legs from one found chair and attaches them to the ends of another, making one absurdly tall and the other comically legless. The height difference implies a hierarchy yet both are made precarious and arguably useless by the modifications. Does more chair make a chair not a chair? How much chair can you remove before a chair is not a chair anymore?

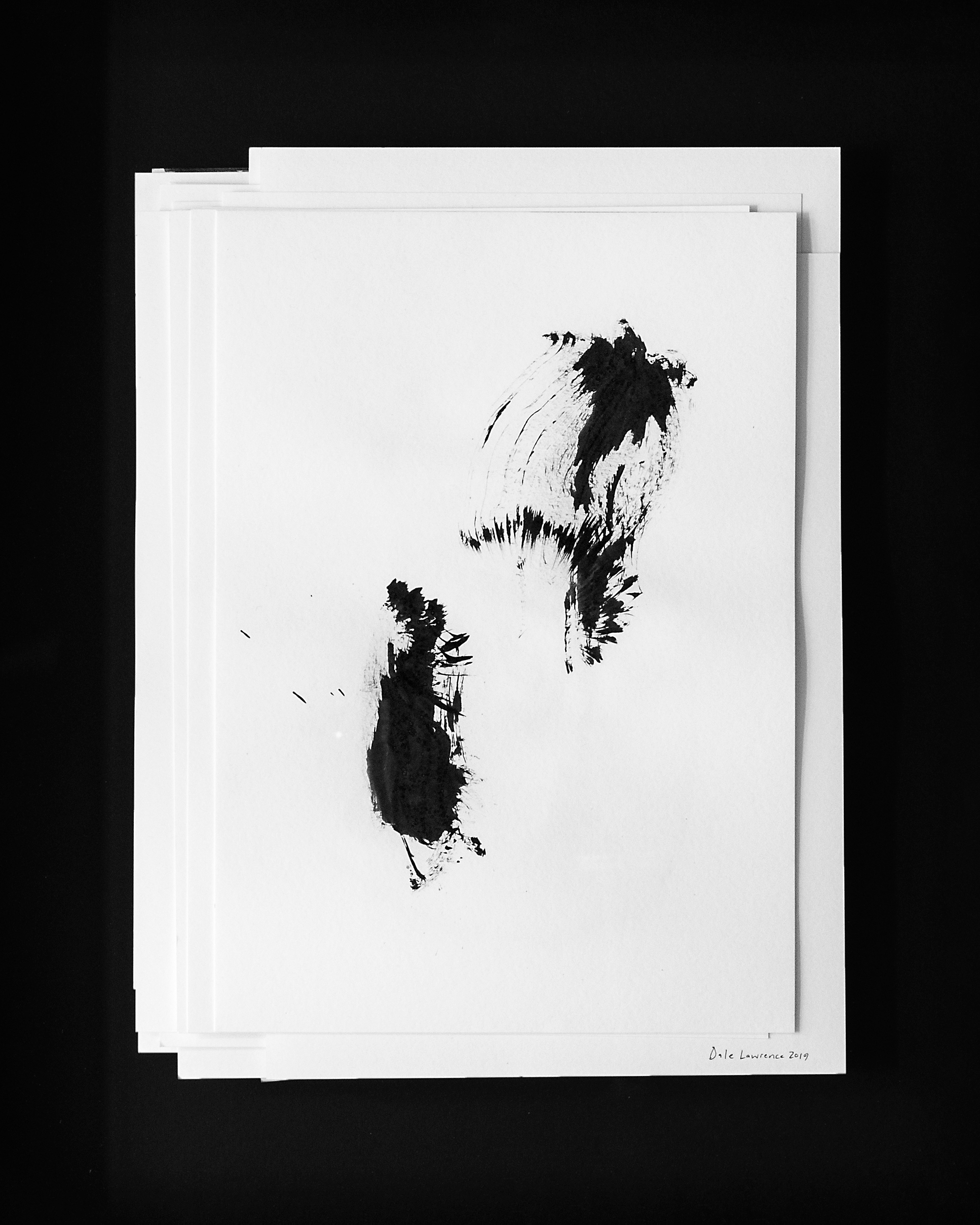

In a series titled Attempts, Lawrence shows a stack of Indian ink on paper drawings, each attempt piled on top of the next. The drawings are gestural and impulsive, full of Lawrence’s trademark concerted playfulness. The sum total of these attempts are presented as works in themselves, their finished-ness abrupt and questionable.

Lawrence’s fat works—for which he avidly carved into slabs of tallow made according to a Joseph Beuys recipe—dig into the idea of fat as both an essential, life-supporting substance and one that signifies superfluity and excess. Self-portrait in Front of the Burning Cathedral references the recent Notre Dame fire and queries the potential of burnt wood as something very much alive and useful. Lawrence’s surface this time is burnt yellowwood, South Africa’s national wood, mirroring the French oak beams used to support the Notre Dame’s spire.

Further Prototypes may speak to Kounellis’s work in one instance most clearly but the kinship runs deeper and permeates the show. Kounellis was famously direct, his work keenly responsive to its time. When invited to inaugurate an upmarket art gallery in the late 1980s, he filled the space by suspending large pieces of ox carcass on iron panels. “I apologise to everyone: I would like to have made an Arcadian landscape, but the times did not permit that,” Kounellis told the curator.

For Lawrence, like Kounellis, art is an occupation and a mirror. It is what it sees. What Lawrence sees is uncertainty, possibility, transience. The magnificent in the mundane, the mundane in the magnificent. A loop with no end, an endless question.

This is one of many curveballs thrown by Dale Lawrence in Further Prototypes, his third solo show at SMITH, the latest stanza in his wry inquiry into the ambitions of art and its practitioners. With Look Busy (2016) and Another Helping (2017), as with his Art Joburg show Amateur Hour (2018), Lawrence scratched at these ideas, studying the tension between focused intent and wilful abandon. Here, he puts the ideas to theatre.

“Finished is dead,” says Lawrence, who chooses instead to work with the vitality of experimentation. Doing so brings action, change, motion and surprise into another distinctively considered collection of mixed media offerings that this time includes imagery variously scratched into animal fat, drawn onto photocopier glass and printed on bread. There’s also a bath in the gallery and, yes, he will bathe in it. Every day for six weeks.

In Seen and Not Seen, the bathtub work, Lawrence will prove his interactions with it without showing them. We will see solely the evidence of his activity; the memory of it. A wet footprint, perhaps, or a crumpled towel. By repurposing the gallery as a working space, a conduit through which Lawrence passes, he draws attention away from the idea of finished works hanging inert on a wall and towards the lively, uncertain environment from which his works are made.

Throughout the show, Lawrence will be otherwise active in the space, working on his largest canvas to date, the 1.75m x 3.5m Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Large Bathers in situ. These elements of his normal life—the painting, the bathing—help to set the show in a state of flux, placing artmaking as a functional part of the everyday. Here Lawrence draws from German artist Joseph Beuys, who considered art much broader than painting, sculpting and exhibiting. For Beuys, as for Lawrence, the impulse to create is seen as a basic component of human life.

“Completeness and incompleteness coexist. We are never finished. Our routines become rituals and our rituals can degenerate into routines. Art is a form of distilling reality, where grand intentions and everyday mundanities are the subjects—with sometimes overwhelming and sometimes underwhelming results.”

Hercules is Lawrence’s playful tracing of a mashup of two classic scenes with similar compositions by Frederic Lord Leighton and Paul Cézanne. Leighton’s horrified characters, Cezanne’s indifferent bathers and finally Lawrence’s cursory retelling of these stories probes at how the function of art has changed. Art used to need to capture critical and epic moments, later just moments. What do we ask of it now?

That this and other works are in fact or appear ostensibly unfinished stems from a disregard for finality that permeates this collection and can be traced further back. Amateur Hour fleshed out an argument that achievement is subordinate to the act of the pursuit thereto. Then as now, pursuit is Lawrence’s first virtue. To arrive is to abandon pursuit, to be finished. And finished is dead.

Lawrence’s use of masterpieces as source material in the show stems from this notion. His respect for striving over finding sees prototypes as new models of thought. The creative sphere is one for experiment and testing, where new ideas and aesthetics are prototyped and test-driven before being adopted in the real world.

“When a work is considered a masterpiece it implies that an idea has been refined to the point of absolute completion and perhaps exhaustion, leaving it short of much of the vitality of the prototype.”

Lawrence’s most pointed jab at this is the work St. Lawrence Handing out the Treasures of the Church, where he treats a photocopy machine’s glass as a printing plate. Viewers of the work will be able to print out a copy of the famous scene, as artist and device stage a modern parody on the doling out of churchly treasures. The cumbersome photocopier is the artist himself, a dubious intermediary through which an original and pure thought must traverse. Repetitions mean diminishing returns. More is less.

“If art is a means by which to pay homage to inspiration it is also proof of the inability of human beings to accurately express the purity of that inspiration. The observer principle suggests that it is impossible to observe a phenomenon without changing it. Art is an interference.”

Portrait of Ideal Self as St. Paul the Hermit, Except Not so Poor and Hungry and Naked and Lonely and Cold is a relief print on a sheet of bread, akin in both substance and design to the communion offering but depicting a figure engaged in a leisure activity. Bread is a basic unit of substance and signifier of spiritual nourishment, yet only represents meaning. It has none in and of itself.

St. Lawrence? Communion bread? Has Lawrence gone all religious on us? The gallery is, after all, art’s church. This is where a form of aesthetic communion is practiced. This is where we gather to drink wine and hear nominated spokespeople muse on the meaning of it all. The substance of the offering depends in some part to the faith we place in the institution that houses it, and of course the person handing us the sacrament. Communion bread is either metaphysical and full of meaning, or vacuous and in dire need of some Marmite.

Or, as Lawrence suggests, lightly salted like a Lay’s crisp. Perhaps the crowning piece of the show is another remake, this time a riff on the 'Tragedia Civile' by Jannis Kounellis. Lawrence uses Lay’s crisp packets where Kounellis used gold leaf to festoon a wall signifying the accomplishments of the past. Lawrence replaces the original’s hook, hat and overcoat with a bowl of Lay’s lightly salted crisps lying on the table for consumption, while a mobile phone lies charging on the shelf instead of a paraffin lamp. This self-administering of communion, a modern offering of no substance in an age of cheap imitation and distraction, wonders at the depth of our dubious relationship with conveyors of meaning.

But accomplishment implies some measure of success and finality, and we know how Lawrence feels about those things. His title for the installation, Tragedy of the Rainbow Warriors, mashes up the original with a newspaper headline marking a supposedly seminal moment in recent South African history. Nelson Mandela, dressed in a Springbok jersey, hands captain Francois Pienaar the 1995 Rugby World Cup trophy. Here is a moment that aimed to tell us something had ended. But was this the end—or the beginning—of anything?

Clearly, Lawrence detects a kind of idiocy in viewing this or any moment as a conclusion or resolution. “We were supposed to feel like something had been solved. We were offered absolution from our sins, cheap closure in a flash. The truth was something a lot less certain.”

Lawrence doesn’t miss this opportunity for another witticism. Noting that we lay our crisps onto our tongues like communion wafers, he nominates a Western brand as our priest. As Apartheid ended and sanctions were lifted, we South Africans were rewarded with a deluge of attractive but empty gifts from the West. The Gods were good to us.

If Lawrence is playing with his use of the pedestal it is more as jester than preacher. Like a king’s clown he agitates, entertains and excites, making himself vulnerable, present and unguarded. Lawrence’s work can also be downright funny. A found ceramic vase lies shattered on the floor beneath its pedestal, surrounded by a handful of rubber bands, the dull accoutrements it was used to contain. The ornate is reduced to a vessel for cheap, functional detritus. A vessel, grand and full of potential, tragically reduced to its base utility. But is an ornament less impressive when it is being used?

With Nameless and Friendless, Lawrence removes the legs from one found chair and attaches them to the ends of another, making one absurdly tall and the other comically legless. The height difference implies a hierarchy yet both are made precarious and arguably useless by the modifications. Does more chair make a chair not a chair? How much chair can you remove before a chair is not a chair anymore?

In a series titled Attempts, Lawrence shows a stack of Indian ink on paper drawings, each attempt piled on top of the next. The drawings are gestural and impulsive, full of Lawrence’s trademark concerted playfulness. The sum total of these attempts are presented as works in themselves, their finished-ness abrupt and questionable.

Lawrence’s fat works—for which he avidly carved into slabs of tallow made according to a Joseph Beuys recipe—dig into the idea of fat as both an essential, life-supporting substance and one that signifies superfluity and excess. Self-portrait in Front of the Burning Cathedral references the recent Notre Dame fire and queries the potential of burnt wood as something very much alive and useful. Lawrence’s surface this time is burnt yellowwood, South Africa’s national wood, mirroring the French oak beams used to support the Notre Dame’s spire.

Further Prototypes may speak to Kounellis’s work in one instance most clearly but the kinship runs deeper and permeates the show. Kounellis was famously direct, his work keenly responsive to its time. When invited to inaugurate an upmarket art gallery in the late 1980s, he filled the space by suspending large pieces of ox carcass on iron panels. “I apologise to everyone: I would like to have made an Arcadian landscape, but the times did not permit that,” Kounellis told the curator.

For Lawrence, like Kounellis, art is an occupation and a mirror. It is what it sees. What Lawrence sees is uncertainty, possibility, transience. The magnificent in the mundane, the mundane in the magnificent. A loop with no end, an endless question.

Further Prototypes: A Mostly Visual Essay

Dale Lawrence – Further Prototypes by Matthew Freemantle (PDF)

All works©2019 Dale Lawrence. All rights reserved